Iditarod National Historic Trail

Iditarod National Historic Trail Collections

Digital records and photographs of the Iditarod National Historic Trail (INHT) may be browsed on the ARLIS document server. Also available are a brief history of the trail and suggestions for further reading.

This collection includes most of the material collected for the creation of the two volume INHT Comprehensive Management Plan (CMP) and Resource Inventory. While only a small percentage of data and photographs appear in the CMP or the Resource Inventory, this collection makes public the rest of the work, which includes high resolution slides, photographs, resource inventories, field notes, and more. Also included are oral history interviews, which feature the voices and stories of men and women who experienced the end of Alaska’s gold era, including participants in the 1925 serum run. Previously unpublished reports included in the collection also add to the mass body of information collected about the Iditarod National Historic Trail.

The information here is useful for research of both history and policy. Much of the data included offers an alternative view into Alaska’s gold rush heyday, examining and substantiating the literature written during and about this period in Alaska’s history. The documentation of these historical resources, as studied in the early 1980s, also offers a window into past preservation tactics, and guidance for the future preservation of Alaska’s history.

Digital Iditarod Collection

- Goodwin Alaska Road Commission Report on the Seward Nome gold trail (1908)

- Bureau of Outdoor Recreation report on the Iditarod and other gold trails (1977)

- Preliminary Inventory of Cultural Resources between Rainy Pass and Unalakleet (1979)

- Environmental Impact Assessment and Findings of No Significant Impacts (1979 & 1981)

- S. M. Peterson Annotated Maps (1981)

- Oral History Recordings

- Oral History Transcripts

- Quadrangle Files (4,500+ files in 750+ folders, including many high resolution slides and photographs)

- INHT Resource Inventory (1982)

- INHT Comprehensive Management Plan (1986)

The Bureau of Land Management Alaska digitized this collection using original documents, maps, slides, photographs, maps, and publications in BLM files on the Iditarod National Historic Trail. BLM Alaska retains the items digitized. Jarod Hoogland worked on much of the collection and wrote the descriptions, metadata, brief history, and the suggestions for further reading, used here in edited form.

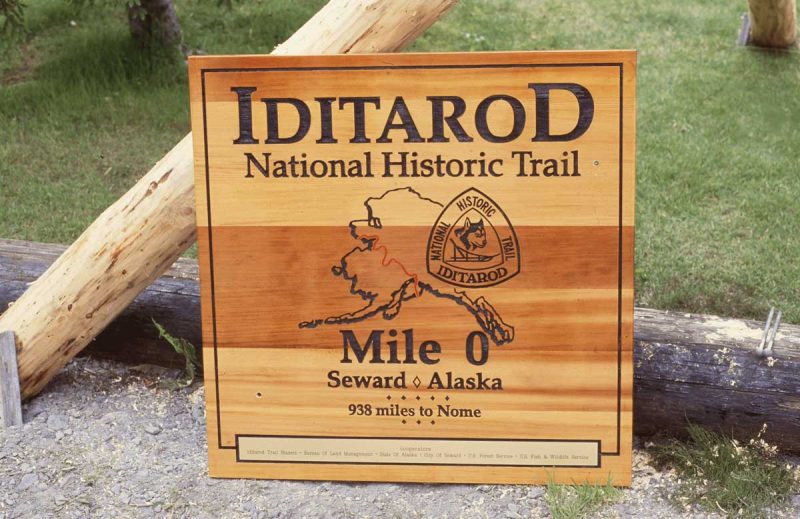

Iditarod mile zero sign.

Unidentified dog sled team at Skwentna.

View of Seward C-6 – the Loop District.

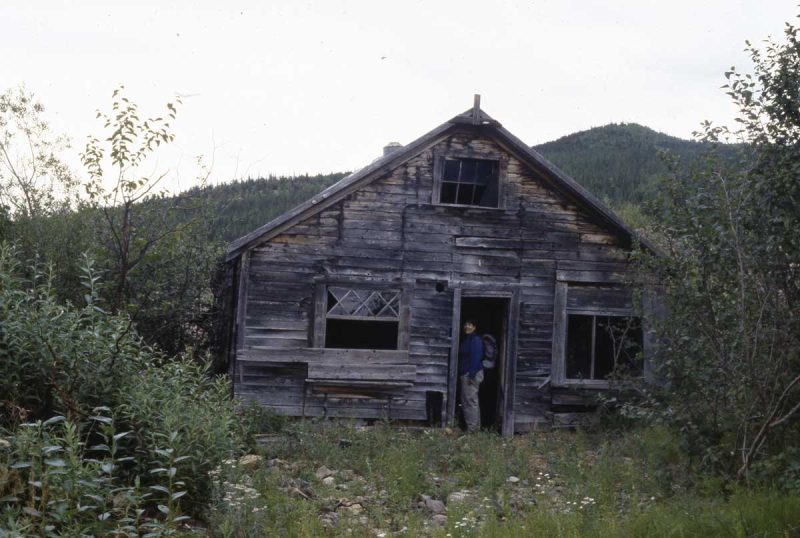

Old house at Flat.

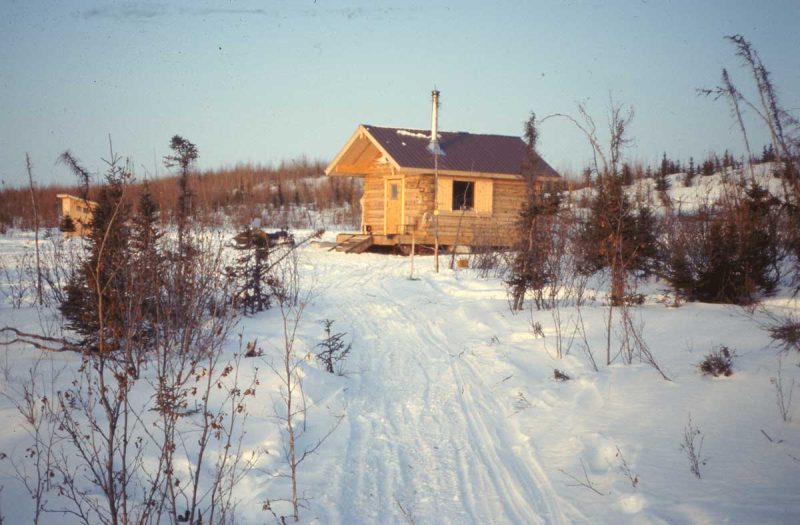

Bear Creek cabin.

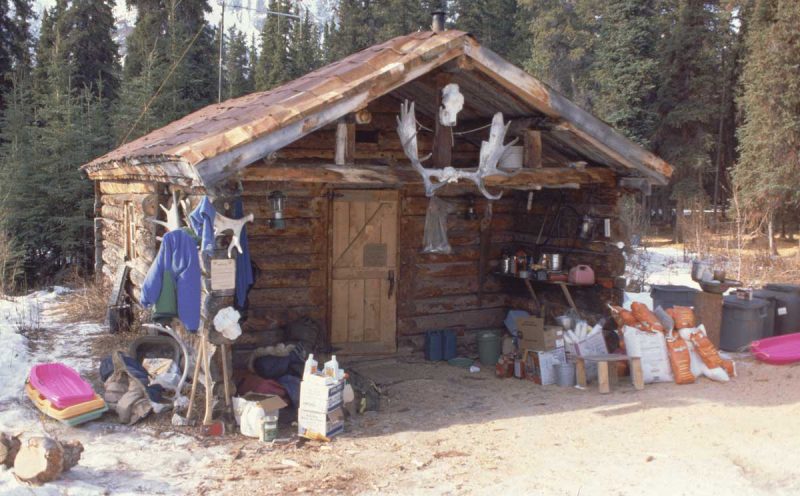

Rohn cabin.

Grave site. Source: INHT Iditarod C-5/IDT-001

INHT: A Brief History

On Christmas Day in 1908, gold was discovered on Otter Creek, a tributary of the Iditarod River. Alaska’s last great gold rush would begin here, far into Alaska’s interior. Nome had already been established because of a previous gold rush, but winter ice prevented maritime traffic for the majority of the year. The only ice free port established at this time was in Seward, a far cry from both Iditarod and Nome. Miners and entrepreneurs were already demanding that the government establish a trail for mail and safe passage. Colonel Walter L. Goodwin and the Alaska Road Commission began work on the trail in 1908, and concluded in 1911. Because expansive river systems allowed access to the Iditarod region in summer months, the trail system was primarily used in winter. The majority of travelers did not complete the entire Seward to Nome route, but rather made their destination the gold rich fields of the Iditarod district, thus the Seward-Nome route became known as the Iditarod Trail.

Dog mushing on the Iditarod Trail was nearing its end by the time Nome had its diphtheria outbreak. Aviation was in its infancy and was quickly becoming the primary means of bush travel. Because of weather conditions, the mushers that remained from the gold era were summoned to complete the relay that would be known as the 1925 Serum run. This was the last great moment for dog mushing for several decades. When the Iditarod Sled Dog Race began in 1973, as an effort to commemorate and promote dog mushing on the Iditarod gold trail, the serum run was also remembered as part of that history. While the original serum run was run from Nenana to Nome, the current race format follows most of the historical trail as mapped by Colonel Goodwin, thus combining the excitement of sled dog racing with the historical past.

The Iditarod National Historic Trail is Established

In 1978 the United States Congress amended the National Trails System Act to include a new category: National Historic Trails. Among its first inductees was the Iditarod National Historic Trail (INHT). The 938 mile Seward-Nome mail route surveyed and constructed by the Alaska Road Commission under Goodwin was established as the primary route. However, the entirety of the trail network, including branches that connect former mining towns, was included under the National Trails System Act, effectively adding hundreds of miles to the INHT.

This sprawling network of trails passes through land owned by various federal and state agencies, as well as Native Corporations, local governments and individuals. Through the amended Act, the Bureau of Land Management was designated as the manager of the INHT, to work in cooperation with all the agencies and individuals who had ownership of the trail. Their collaborative effort to establish a management philosophy culminated in the publication of the INHT Comprehensive Management Plan (CMP) with the accompanying INHT Resource Inventory.

The INHT CMP and its accompanying volume INHT Resource Inventory have two purposes. The first is to document as many historical sites on the trail system as possible. BLM, in conjunction with its agency partners, sent several expeditions out to the trail between 1978 and 1981. Sites that were identified in historical literature and oral histories were first located by air, and in many cases, further studied on the ground. The location and remaining structures at these sites were documented and photographed. In some cases, these were the last photographs captured at particular sites, as fire damage and river erosion destroyed what was left of its remains.

The second purpose of the INHT CMP was to develop management proposals for each individual site. Each recommendation was based on the condition of the site, as well as potential visitor use and accessibility. Based on these recommendations, the BLM and its partners maintain and protect various site locations. One such location is the Rohn River Shelter Cabin, originally built in 1939, which is still used today as a checkpoint in the annual Iditarod dog sled race.

The Iditarod National Historic Trail Collection at ARLIS

The digital INHT collection at ARLIS includes most of the material collected for the creation of the INHT CMP. While only a small percentage of data and photographs appear in the INHT CMP and INHT Resource Inventory, this collection makes public the rest of the work, which includes all photographs, resource inventories, field notes, and more. Also included are the oral history interviews, which feature the voices and stories of men and women who experienced the end of Alaska’s gold era, including participants in the 1925 serum run. Previously unpublished reports included in the collection also add to the mass body of information collected about the Iditarod National Historic Trail.

The information here is useful for research of both history and policy. Much of the data included offers an alternative view into Alaska’s gold rush heyday, examining and substantiating the literature written during and about this period in Alaska’s history. The documentation of these historical resources, as studied in the early 1980s, also offers a window into past preservation tactics, and guidance for the future preservation of Alaska’s history.

Jarod Hoogland, Anchorage, 2009, edited by Steve Johnson, 2011 and 2014.

Further Reading

Primary Sources

There are many good resources for studying the history of the Iditarod National Historic Trail (INHT). This bibliography is by no means exhaustive. Its purpose is to introduce the primary sources used in the creation of the INHT Comprehensive Management Plan, as well as a few other useful pieces.

The main categories of primary sources for the INHT are: Journals, historic newspapers, oral testimony, and government reports.

The main source for information regarding Alaska before the U.S. purchase is Lieutenant Zagoskin’s travels in Russian America, 1842-1844 : the first ethnographic and geographic investigations on the Yukon and Kuskokwim Valleys of Alaska, published for the Arctic Institute of North America by University of Toronto Press, 1967. This book, available at ARLIS, is an excellent read, detailing the reconnaissance conducted by Zagoskin on behalf of the Russian America Company. His travels up Alaska’s major river systems in an effort to survey sites for trading posts led him to many encounters with Alaska native communities and their trade routes. Many of these traditional routes would later be used by miners traveling to the Iditarod district, and would become part of the INHT. Zagoskin also provides information on the evolution of dog mushing, detailing Russian influence on the popular means of travel. It was Russian influence that provoked the use of a lead dog with symmetrical harnessing and the creation of the modern sled design.

When locating historical sites on the INHT, BLM researchers often turn to the 1908 Goodwin Report, which is provided here in PDF format. Here, Goodwin documents existing roadhouse sites, future roadhouse sites, potential sites, and the mileage between all of them. Within the report it is mentioned that several entrepreneurs followed the Russian America Company expedition in hopes of establishing roadhouses along the way. This report was very accurate, and often BLM researchers were led to site locations by following the information found in this report. This report is included in the digital collection.

10,000 Miles with a Dog Sled is another journal used extensively by BLM researchers. Hudson Stuck, an Episcopal Archdeacon, traveled extensively throughout the interior of Alaska, encountering many of the area’s gold rush towns and native communities. The records found here are compared to those provided by Goodwin and others to measure the accuracy of place locations and events.

Wherever gold brought a rush of people, there is always an opportunity for journalism. This proved true in the early communities of Nome, Seward and Iditarod, to name a few. Newspapers in these communities often were short lived, but the information they carried, while entertaining for miners, provides researchers today a wealth of knowledge about local traditions, politics, and culture. Many of these newspapers can be found on microfiche at UAA. A few of the most prominent include Iditarod Pioneer, Iditarod Nugget, Seward Gateway, and Nome Nugget. Additionally, magazines such as the Alaska Yukon Journal, Alaska Sportsman, and Alaska Magazine carry original stories told by men and women who lived along the INHT.

The oral histories collected by the BLM are infinitely valuable, particularly since the people interviewed are often not authors, and having their stories caught on tape may have been the only way to permanently preserve their past experiences. It is also a completely different experience to hear the original spoken words of a miner, with all its nuances and inflections that are often lost in the printed word. Oral history recordings, and transcripts of same, are available as part of the Iditarod Collection in mp3 and PDF format.

For reports on the gold fields of the Yukon and Alaska, see three accounts by Josiah Edward Spurr, available in print at ARLIS. Some of Spurr’s reports are also available on Google books.

Spurr, Josiah Edward. Through the Yukon gold diggings; a narrative of personal travel. Boston: Eastern publishing company, 1900.

Spurr, Josiah Edward and Harold Beach Goodrich. 1898. Geology of the Yukon gold district, Alaska. Washington: Government printing office, 1898.

Spurr, Josiah Edward, and F. C Hinckley. 1900. A reconnaissance in southwestern Alaska, in 1898. Washington, D.C. : Govt. Printing Office.

Jarod Hoogland, Anchorage, 2009